- Measures adopted during the pandemic do not address the root causes of the problems facing higher education.

- Institutions need to undertake true reform, moving towards active learning, and teaching skills that will endure in a changing world.

- Formative assessment is more effective than high-stakes exams in equipping students with the skills they need to succeed.

- Replacing lectures with active learning

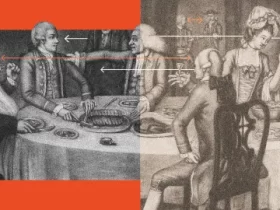

Lectures are an efficient way of teaching and an ineffective way of learning. Universities and colleges have been using them for centuries as cost-effective methods for professors to impart their knowledge to students.

However, with digital information being ubiquitous and free, it seems ludicrous to pay thousands of dollars to listen to someone giving you the information you can find elsewhere at a much cheaper price. School and college closures have shed light on this as bad lectures made their way into parents’ living rooms, demonstrating their ineffectiveness.

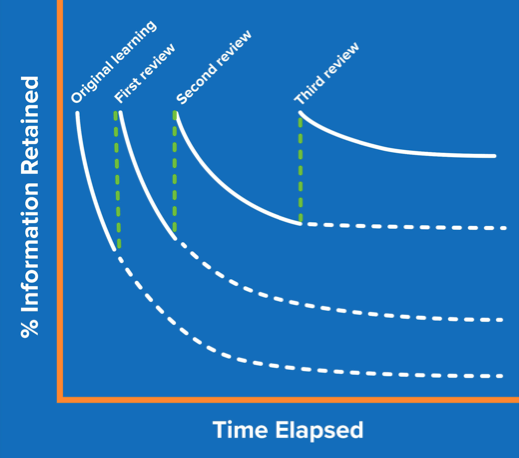

Education institutions need to demonstrate effective learning outcomes, and some are starting to embrace teaching methods that rely on the science of learning. This shows that our brains do not learn by listening, and the little information we learn that way is easily forgotten. Real learning relies on principles such as spaced learning, emotional learning, and the application of knowledge.

Higher education is beginning to accept that traditional methods of teaching are ineffective – as demonstrated by the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve

The educational establishment has gradually accepted this method, known as ‘fully active learning’. There is evidence that it not only improves learning outcomes but also reduces the education gap with socio-economically disadvantaged students. For example, Paul Quinn College, an HBCU based in Texas, launched an Honors Program using fully active learning in 2020, combined with internships at regional employers. This has given students from traditionally marginalized backgrounds the opportunity to apply the knowledge gained at university in the real world.

2. Teaching skills that remain relevant in a changing world

According to a recent survey, 96% of Chief Academic Officers at universities think they are doing a good job preparing young people for the workforce. Less than half (41%) of college students and only 11% of business leaders shared that view. Universities continue to focus on teaching specific skills involving the latest technologies, even though these skills and the technologies that support them are bound to become obsolete. As a result, universities are forever playing catch up with the skills needed in the future workplace.

What we need to teach are skills that remain relevant in new, changing, and unknown contexts. For example, journalism students might once have been taught how to produce long-form stories that could be published in a newspaper; more recently, they would have been taught how to produce shorter pieces and post content for social media. More enduring skills would be: how to identify and relate to readers, how to compose a written piece; how to choose the right medium for your target readership. These are skills that cross the boundaries of disciplines, applying equally to scientific researchers or lawyers.

San Francisco-based Minerva University, which shares a founder with the Minerva Project, has broken down competencies such as critical thinking or creative thinking into foundational concepts and habits of mind. It teaches these over the four undergraduate years and across disciplines, regardless of the major a student chooses to pursue.

3. Using formative assessment instead of high-stake exams

If you were to sit the final exam of the subject you majored in today, how would you fare? Most of us would fail, as that exam did not measure our learning, but rather what information we retained at that point in time. Equally, many of us hold certifications in subject matters we know little about.

Many people gain admission to higher education based on standardized tests that skew to a certain socio-economic class, rather than measure any real competency level. Universities then try to rectify this bias by imposing admission quotas, rather than dissociating their evaluation of competence from income level. Many US universities are starting to abandon standardized tests, with Harvard leading the charge, and there have been some attempts to replace high-stake exams with other measures that not only assess learning outcomes but actually improve them.

Formative assessment, which entails both formal and informal evaluations through the learning journey, encourages students to actually improve their performance rather than just have it evaluated. The documentation and recording of this assessment include a range of measures, replacing alphabetical or numerical grades that are uni-dimensional.

Leave a Reply