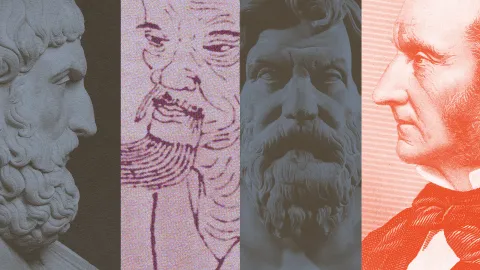

Philosophy can often seem overly concerned with terribly abstract questions, such as whether chairs truly exist. However, the questions of philosophy cover all areas of human interest. Perhaps most importantly, several philosophers have spent time on the question of how to live a happy, even joyful, life. Here, we look at four such philosophers, their ideas, and whether they took their own advice.

Zhuangzi on being more “spontaneous”

Zhuangzi is both the name of a Taoist philosopher and a book on Taoist philosophy. The book was written sometime during China’s Warring States period (476–221 BC), and its influence made Zhuangzi, its author, the second most important Taoist philosopher after Laozi. As a Taoist, Zhuangzi argues for living more harmoniously with the Tao, the underlying order of the cosmos in Taoism. He also suggests that the path to a joyful life is to be more spontaneous.

For most of us, spontaneous has a meaning not too dissimilar from “impulsive,” but this is not how Zhuangzi uses it. In the Taoist fashion, it is understood by coming to terms with its opposite.

Zhuangzi gives us the example of a butcher who trains for years until he can spontaneously cut meat without thought. He becomes so good at his work that he doesn’t even have to sharpen his knife anymore. Spontaneous doesn’t mean “impulsive” here, but something closer to “instinctive.” Zhuangzi encourages us to train ourselves until we don’t have to think about our actions and intuitively know how to act.

Zhuangzi argues that this tendency — which many of us will recognize in our hobbies and even driving along familiar roads — can be applied to every aspect of our lives, no matter how mundane. In doing so, we can understand the Tao in our lives and experience joy in the little things. He further advises that we learn to take many perspectives on the world and avoid egocentrism.

It is difficult to know if Zhuangzi took his own advice. As with many ancient philosophers, we know little about him that is reliable; however, if the brilliance of his writing is any indication — with its skillful wordplay and irony — he seems to have mastered spontaneity comparable to his master butcher. His calls to consider the world from diverse perspectives and to understand our connection to everything else also seem to come from a place of understanding.

Antisthenes on living virtuously

A student of Socrates, Antisthenes would go on to become the founder of the Cynic school of philosophy.

Advancing from the Socratic notion that virtue is the key to happiness, Antisthenes argued that virtue was enough for happiness. He further argued that pleasure was often a bad thing as it makes a person incapable of self-reliance, instead nurturing dependency on whatever provides those enjoyable sensations. He claimed to prefer madness to pleasure and taught the benefits of living a simple, self-sufficient, virtuous life.

Since cynicism is known as an extreme philosophy, it isn’t easy to provide a practical take on this advice that is also appealing. Remember, the goal here is “happiness” as in a life well lived. It is not necessarily the notion that you’ll feel great all the time. Having said that, Antisthenes does provide advice anyone could use.

First, he argued that virtue could be taught, so the wise man should begin studying it immediately. At the same time, he valued action over mere words. He felt that pain and a bad reputation could be useful in avoiding pleasure. He even said that social rules and the law could be ignored in favor of virtue. In all, it adds up to turning away from a great deal of society. However, some sources report that he also encouraged marriage and childbearing as part of a well-lived life.

True to his teachings, Antisthenes chose to live in poverty and allegedly devised the idea of folding a cloak twice so it could be slept in. He had a sharp wit, and his use of humor to skewer Athenian culture was well known. His more famous student, Diogenes, would dial his teacher’s ideas up to 11 and seemed fairly happy while doing so. Your results may vary.

Epicurus on extremely moderate hedonism

Epicurus was a Greek philosopher working around 300 BC. Opposed to the then-dominant Platonism, he formulated ideas on everything from justice to physics, but his most famous are about how to live well. Epicurus argued for hedonism — that the good life is one characterized by the pursuit of happiness. However, this isn’t the kind of drunken hedonism associated with a Greek symposium.

Unlike the Cyrenaics, Epicurus argued that the thinking hedonist must consider the long-term viability of their pursuit. Given the choice between satisfying a desire or removing it, Epicurus suggests you try the latter whenever possible. He encourages moderation in all areas of life and learning to be content with satisfying desires rather than seeking luxury. His take on happiness might be better considered “tranquility” rather than “pleasure.”

As more practical advice, Epicureans tended to live together in communities where they often allowed women and slaves to join (a rarity in the ancient world). He praised friendship, even if he thought it was a tool for individual pleasure, and encouraged living with your friends. He also encouraged taking simple measures to solve desires, such as enjoying moderate meals over lavish feasts — the former, he argued, being much more sustainable and so leading to more happiness over time. However, he also permits moderation to be moderated and does not insist that you have to continuously live like a pauper.

Epicurus lived his philosophy as any good Greek philosopher would. He lived in a school he founded called “The Garden,” enjoyed a moderately ascetic lifestyle, and led his students in community activities. By all accounts, he seemed to enjoy doing so.

John Stuart Mill on higher and lower happiness

John Stuart Mill was a 19th-century English philosopher, economist, and member of Parliament well known for his stances on liberalism, feminism, and ethical philosophy. He advanced the then-fairly new philosophy of utilitarianism.

As put forward by its founder, the eccentric Jeremy Bentham, utilitarianism argues that the only ethical “good” is pleasure and the only ethical “bad” is pain. The right thing to do in any given situation is that which will maximize total pleasure. For Bentham, any pleasure is as good as any other, and the only question is how much of it there is. His view would be simplified as: “Pushpin is as good as poetry.”

However, Mill disagreed with Bentham on the idea that any pleasure is equal to any other. Instead, he viewed pleasures as belonging to “higher” and “lower” categories. Generally, “higher” pleasures are mental, moral, and aesthetic; “lower” pleasures are more sensual; and for those capable of enjoying both, a higher pleasure is always the qualitatively better choice.

As such, he argues that we should look to the higher pleasures over the lower ones when trying to maximize total happiness, both in our lives and for the world at large. This requires we develop the capacity to enjoy the higher pleasures, actively choose them over the lower ones, and try to avoid causing pain. Having too much to drink might make us giddier than reading Elliot, but for Mill, the latter is a better choice nearly every time while not leaving us hungover.

For his part, while not adverse to “lower” pleasures, Mill certainly spent a great deal of time with the higher ones. He enjoyed reading poetry, especially William Wordsworth, and corresponded with many thinkers who worked in fields different from his own.

Leave a Reply